Shades of Conflicts Past

Don McCullin has collected his images from a life on the battlefront in “Sleeping With Ghosts”

By Tom Burton

As his deadline approached, British war photographer Don McCullin still did not have a title for his latest book. At his home in Somerset, England, were cabinets full of negatives and prints depicting some of the most horrific events of the last 30 years. From this morgue he had pulled together 183 photos.

The wars he had witnessed made McCullin famous, but the tragedies had become haunting memories he couldn't forget.

''They are nightly visitors to me, those people in the photos,'' McCullin said. ''I swear to God that I can sometimes hear those cries.''

Eventually, McCullin knew that “Sleeping With Ghosts” (Aperture, $45) was the title he was looking for. The resulting book is an epic collection of black-and-white photos dating from the early 1960s showing a wide range of conflicts including wars in Cyprus, Biafra, Northern Ireland, Vietnam, Cambodia, Beirut and Iraq.

Now 60, McCullin doesn't go to war anymore. He has left behind the danger and adrenaline of crisis journalism and is starting a new chapter in his life. He recently married Marilyn Bridges, an American art photographer, and is experimenting with landscape and still-life photography.

In a telephone interview from Bridges' home in upstate New York, McCullin said he never felt that his photos should be printed on anything other than the cheap newsprint used in The Destruction Business, his first book in 1971.

A high-quality coffee-table book seemed out of the question.

But Sleeping With Ghosts, his 12th book, is exactly that. McCullin admits the hypocrisy but adds a disclaimer.

''Any coffee table it sits on is going to excrete some kind of unhappiness,'' McCullin said.

McCullin is often described as the heir of Robert Capa's title as the ultimate war photographer. Capa's famous work from the D-Day invasion in World War II helped secure his legend. Capa died in Indochina in 1954 when he stepped on an anti-personnel mine.

Capa's brother Cornell Capa, founder of the International Center of Photography, says McCullin is deserving of the comparison.

''The bravery and compassion of Don McCullin is just as legendary as my brother's,'' Capa says.

''Don McCullin lives Robert Capa's dictum, 'If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough,' '' Capa says. ''McCullin's photographs are 'close enough.' ''

Marianne Fulton, chief curator for the George Eastman House, agrees that McCullin's photos work because of an intense intimacy.

''His work has a special quality. It is part of his attitude. Part of it is 'in your face' and it can be very horrific because he's so close,'' Fulton says. ''You feel some of the suffering of that person. It's like being slapped in the face yourself.''

In 1992, McCullin wrote an autobiography, Unreasonable Behaviour, in which he told the story of his tough childhood in North London and his later attraction to violent situations.

McCullin writes that he was ''born in the thirties and bombed in the forties.'' German war planes created the bomb craters that became his playgrounds.

When the war ended, he moved from school to school where unsympathetic schoolmasters beat him for doing poorly. He could barely read and later discovered he had dyslexia, a reading disorder.

By age 14, he had won an art school scholarship that he soon had to give up when his 40-year-old father died of lung disease. McCullin went to work on the railroad as a pantry boy to help support his family.

As a teenager, McCullin began to hang out with a group of thugs who called themselves the Guvnors. After a brief stint in the British Royal Air Force, McCullin returned home with a Rolleicord camera he had bought with his wages.

Not much had changed with the Guvnors except they now had a fondness for fedoras. Fancying themselves as Dillinger-style dandies, they talked McCullin into making photos of them.

Shortly afterward, a policeman was killed and youth gangs were suspects. The Observer newspaper ran McCullin's photos of the Guvnors in 1959 to illustrate a story on youth gangs. His career in photojournalism had started.

It wasn't long before he was a staff photographer. Seeking both career recognition and adventure, McCullin sought out war assignments. He wanted to win a Pulitzer prize with a John Wayne attitude.

If he had never changed this attitude, McCullin could have been just another photographer. Or a calloused war veteran like his younger brother, who became a mercenary in the French Foreign Legion.

McCullin went on to win many journalism awards but not a Pulitzer. But as he got involved in war coverage, McCullin became more aware of issues and the victims. As he toned down his cocky attitude, his photos became more compassionate.

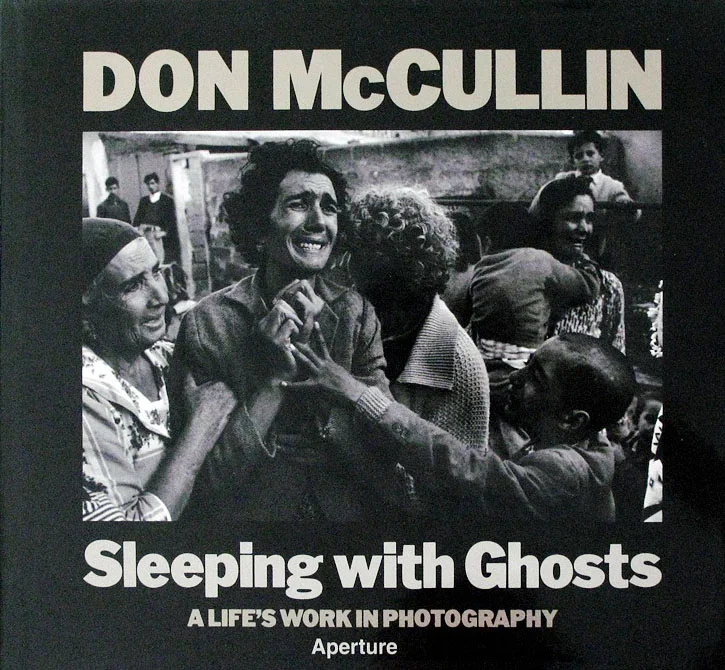

One of his best-known photos, the cover of Sleeping With Ghosts, shows this empathy. Photography curator Fulton calls it ''one of the best pieces of photojournalism ever.''

The photo is from the 1964 civil war in Cyprus and shows a woman grimacing as she hears her husband has been killed. A young boy, perhaps her son, reaches to her from one side and a pair of women surround the widow. All of the faces turn toward her and all of the arms reach for her.

This beautifully structured photo, made in the frantic environment of a war zone, is indicative of McCullin's talent for making careful compositions while bullets are flying around him.

Throughout the years, McCullin became very good at covering wars. But he paid a price for the photos. He was injured by mortar fragments in Cambodia, broke his arm in El Salvador, suffered from malaria more than once and was held prisoner by Idi Amin's troops for four days, facing the very real possibility of execution by sledgehammer.

His family life also suffered. He divorced his first wife, Christine, leaving her for a younger woman. McCullin later faced severe guilt when Christine died from lung cancer. It is a guilt that he still hasn't overcome. Her death also changed his perspective.

''My confidence started dying with Christine,'' wrote McCullin in his autobiography. ''I realized that you could shoot photographs until the cows came home, but they have nothing to do with real humanity, real memories and real feeling.''

Today, McCullin hopes to make a new career from the landscape and still life photos he's shooting.

The final chapter of Sleeping With Ghosts shows his start at this, featuring landscapes with dark, brooding skies and still lifes of flowers and icons resembling memorials.

Some observers think the change to a more tranquil subject may be McCullin's biggest career challenge. Cornell Capa, the surviving brother of a war photographer, put it this way:

''It is very difficult to be a great war photographer and to (then) photograph peace.''

Originally published in the Orlando Sentinel