Art of War

Steve Pi's sculptures focus on two themes—the beauty of dance and the horrors of battle

By Tom Burton

The plaster was heavy. It encased Cpl. Steven Piscitelli's mangled left arm and all of his right leg where his knee had been blown out from behind. The body cast stabilized his back where shrapnel was lodged within an inch of his spine. It so engulfed him that on their first visit to the veterans hospital, Piscitelli's parents walked by without recognizing their son who had just returned from Vietnam.

At the foot of his bed, a small black-and-white TV sat on a tray table. Piscitelli, the 19-year-old macho Marine, was hoping to watch some action or sports show. But on the grainy screen that day in February 1970, a ballet was airing. And Piscitelli, buried in plaster and pain, couldn't move to change the channel.

On TV a ballerina leaped effortlessly across the stage as if she could fly.

To this day, Piscitelli doesn't know who the dancer was, but her image stayed with him. As he studied her beauty, her movement and her grace, he found a way -- for at least a moment -- to forget thousands of nightmares. God knows, he needed to.

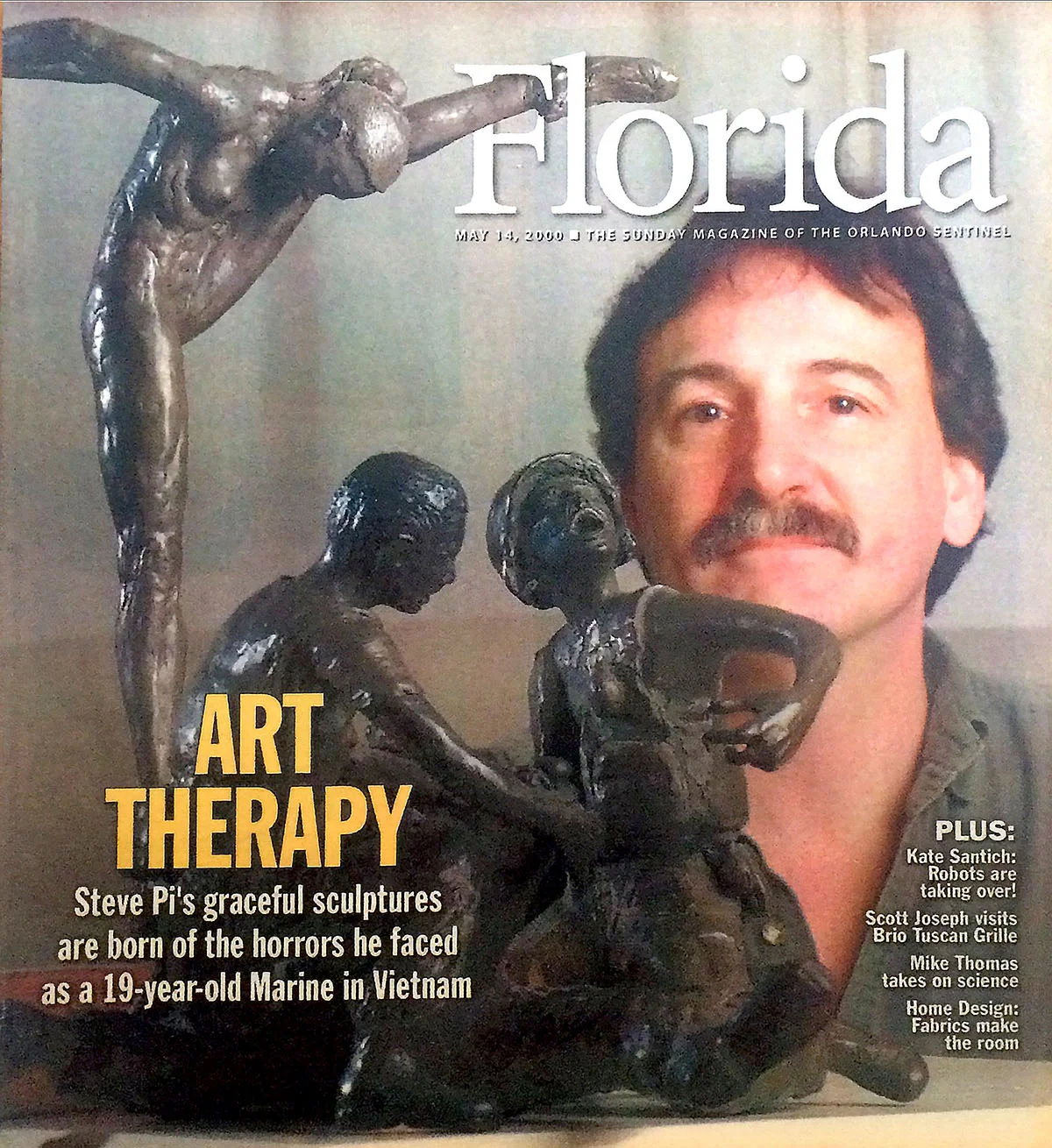

STEVE PI IS THE SHORTENED SIGNATURE Piscitelli now uses as an artist. He has lived in Florida since 1991 and is best known for his bronze sculptures re-creating ballet dancers, much like the one he saw in the hospital ward 30 years ago. His most prominent piece is a larger-than-life dancer on display outside the Southern Ballet Theatre studios in downtown Orlando.

Pi calls the piece ``Wendy" after the athletic bartender who posed for it. The sculpture depicts a ballerina balanced on one foot, her toe pointed in a classic pose. Her arms are like wings, her face joyfully looking to the sky. It is a pose that is amazing for a dancer but seemingly impossible for a statue as the weight of the bronze balances on a single point.

Pi also has created desktop statues that Southern Ballet presents as achievement awards. And a bronze bust he did of musician Frank Zappa is on display at the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg.

His style of intricate, exacting realism is a talent recognized by one of his first art instructors, who noted that as a student Pi could outsculpt his professors.

``He was remarkably talented. I saw he had good hands," said Norman P. Phillips, a retired art instructor at the University of Massachusetts. ``He could model realistically with an extraordinary sensitivity."

Pi's work always has two themes -- dancers and war.

On the shelf above the worktable in his studio are dozens of sculptures in various stages of completion. Clay models and wax forms share space with heavy bronze statues. On the left are dancers in tutus standing on point and others caught in a grand jete leap like the one he saw on TV. On the right are tortured figures -- battle-fatigued soldiers collapsed on their weapons or crying a silent scream.

``I dealt with war imagery by making statues of what was bothering me," he said. ``In order to counterbalance that depressing, miserable subject, I took the most beautiful form of human endeavor, which is dance, and began making dancers just simply as a balance.”

For Steve Pi, art is not simply his craft. It is his salvation.

PISCITELLI GREW UP IN PATTERSON, N.J. His father Mario was a sign painter, his mother Ginger a librarian. They had nine children including Steve, born in 1950. Mario Piscitelli said his son was a quiet child who liked to make things like model airplanes and dinosaurs out of clay.

He was an altar boy known for his keen sense of duty -- and his stubborn streak. Steve always wanted to do things his own way. As he neared the end of high school, his father thought he needed more discipline. Military service had been a tradition for generations of Piscitelli men, and Mario believed the armed forces would help his son. But he knew Steve wouldn't go along with someone else's suggestions for his life. So the father gave the teenager this challenge:

``I made a bet with him that he would never get into the Marines.”

Steve took Dad up on the bet. He dropped out of high school his senior year and joined the Corps.

He tested well after boot camp in Parris Island and spent a few more months being trained in special weapons techniques. He learned to speak Vietnamese. By the time he was deployed to Southeast Asia in May of 1969, Steve had been promoted to corporal.

Though he was trained to be a soldier, Piscitelli was still a kid at heart. He was only 19. He liked to goof off with another Marine who had come to Nam at the same time. Pfc. Dan Bullock was bigger, faster and stronger, but the scrappy Piscitelli always got in his face, always wanted to shadow box with him. A lot of the troops didn't like Bullock. He seemed more like a pesky little brother than a real soldier.

``He was a strange character in that he didn't speak," Piscitelli said. ``He didn't talk about his past.”

Three weeks after they arrived in Vietnam, Bullock and Piscitelli were sparring again. It was about 4 p.m. as they waited for word on that night's patrol. Bullock got in a good jab, dislocating Piscitelli's thumb.

Because of his injury, Piscitelli was assigned to stand guard over tanks several hundred yards from the runway where the rest of his company was stationed. Bullock joined the others in the bunkers. That night, enemy soldiers bombed those bunkers. Bullock and three other men died, 20 were wounded.

Weeks later Piscitelli's company received a copy of the June 13, 1969 New York Times. The front page included a story and photo of Dan Bullock. He had become the youngest American soldier killed in the war. He'd lied about his age. He was 14 when he joined the Marines. The boy's impoverished parents hadn't known he'd signed up. Once they found out, they kept quiet because Dan was hoping to get an education through the military. He was 15 when he died.

AFTER DAN'S DEATH, PISCITELLI CONTINUED his tour in Vietnam. Each day seemed to bring another assault on his values. Men died. Bombs dropped indiscriminately. Blood, violence and death were everywhere.

After three months, he suffered a nervous breakdown. ``All my belief systems were shattered," he said. ``There was no God.”

His breakdown could have sent him home. But Piscitelli didn't tell anyone about his emotional state. Marines live by a code. Proud warriors don't walk away.

``For a Marine to elect to leave combat for psychological reasons is a mark of cowardice," Piscitelli said. ``It's better to be killed than a coward.”

So he rebuilt himself into a pure warrior. He was sure another breakdown was imminent, so he prepared to die before that happened. He became reckless and fierce. During combat raids all he could do was shriek. The danger became a drug. Killing and violence were the high, getting back alive was the only goal. ``It was a heightened sense of existence," he said. "It's not like anything I've experienced before or since. And it was a strange sense of euphoria to survive it.”

He suffered shrapnel wounds on Dec. 16, 1969, and was evacuated with malaria on Christmas Eve. But by February he was back on patrol. On Feb. 10 around 7 a.m. Piscitelli was out searching for enemy patrols in a series of minefields. Another Marine was leading the group, but he was circling outside the area, scared to go in. Piscitelli was impatient and took the point. He led them into an abandoned hamlet.

He noticed a sack of six olive drab uniforms with enemy patches and picked them up. They were booby-trapped. The bomb shattered Piscitelli's back, arm and leg. After nine months in Vietnam, the 19-year-old Marine was sent home.

IT TOOK PISCITELLI FOUR MONTHS TO LEARN to walk again. It will probably take a lifetime for him to heal inside.

He couldn't feel anything when he returned from Vietnam. ``When I came home, my mother tried to hug, but I couldn't," he said. ``There was no emotion.”

It didn't get better. By the time Piscitelli was 33, he had held 40 jobs. He lived in the woods for awhile. He walked the streets armed with a rifle. He lived in a small New York apartment crowded with other war vets.

He talked often about what he'd seen in Vietnam, but the stories seemed too horrible, too brutal. ``When he first came back, he would tell us different tales," says his mother, Ginger. ``It was too strange, it was almost unbelievable." It wasn't until years later when the family saw movies like Platoon that they recognized the scenes. They were the same stories Steve had been talking about.

``We had to believe him then, didn't we?" Ginger Piscitelli said.

He couldn't sleep. When he did doze off, he suffered nightmares. One day an exhausted Piscitelli was working as a banquet chef when a prankster in the kitchen tossed a potato at him and yelled ``grenade!" Piscitelli had a flashback and saw a real grenade coming at him. He threw a large kitchen knife at his attacker. He knows that if his co-worker hadn't ducked, Piscitelli would have gone to jail. Instead, he walked away from the job and decided to go home to New Jersey.

``He came down from New York and he was crying and crying," said his mother. ``He just couldn't stop.”

The family took him to a Vet Center in New Jersey. They, in turn, sent him to a veterans hospital in Massachusetts for psychiatric help. The diagnosis: post traumatic stress syndrome, an ailment that has plagued soldiers for decades but was only recently understood as a mental illness.

As early as the 1800s, soldiers were treated for ``exhaustion" when they became emotionally frozen on the battlefield. After the Civil War, a doctor identified ``soldier's heart" to explain the unexpected rapid heartbeat in veterans years after the battles were over. Other Civil War vets who were haunted by uncontrollable combat memories were said to suffer from ``nostalgia." World War I soldiers had ``shell shock," World War II vets ``combat fatigue." None of the anxieties were thought to require treatment. Soldiers were supposed to be fearless. Most who suffered from combat-related anxiety were told to get over it.

But in 1980, five years after the end of the Vietnam War, the American Psychiatric Association identified post-traumatic stress disorder in its manual of recognized mental illnesses. The disorder starts with exposure to catastrophic stress such as rape, torture, disasters or war. The problem occurs when the body continues to react long after the traumatic situation has passed. Victims often have difficulty concentrating, are prone to angry outbursts, cannot sleep and are easily startled. Flashbacks are perhaps the most frightening symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

TO TREAT THE CONDITION, THERAPISTS must help victims incorporate the traumatic event into their daily lives. Sufferers have often hidden their feelings for years because they were afraid to relive the trauma or were embarrassed by the flashbacks. But experts say to heal, victims must express what they went through.

For some, putting horror into words is difficult. And in those instances, therapists have successfully used art therapy. For these people, drawing pictures, writing poems or even singing songs marks the first step toward confronting their fears.

On his first day at the veterans hospital, Piscitelli noticed Dr. Deborah Golub, an art therapist, walking through the ward. She carried a book on the artist Matisse. Piscitelli told her he didn't think Matisse was exceptional because his drawing was too simple. To prove his point, Piscitelli took a pen and made a quick Matisse-styled line drawing. See, anyone can do that, he told the doctor. Over the next days, he continued talking with Golub and showed her drawings he'd made in the styles of other artists, like DaVinci.

"She got pretty upset because she wanted me to draw what was inside me," instead of copying other artists' work, Piscitelli said.

Her rejection angered him, so over a weekend Piscitelli drew four scenes from Vietnam. One watercolor showed a soldier as a landmine blew off his legs. Another showed a soldier who had been standing near the same explosion. He flailed his arms about, discovering his hand was missing. Piscitelli also drew two self-portraits based on his experiences of war. In one picture he stood over bloated, fly-infested bodies. His hand covered his mouth and nose to ward off the stench. In the other portrait he carried the body of a dead Vietnamese baby.

That weekend, it didn't occur to Piscitelli that art could help him. He was simply drawing out of anger, responding to the chiding of the art therapist that he ought to do his own work instead of copying the masters. But when he saw the hospital staff's reaction to his art -- and the reaction of fellow vets -- he realized its power not only to express the horrors of war but also to help him heal.

"I had been telling these doctors about incidents in Vietnam that I couldn't shake (from memory) and they weren't listening," Piscitelli said. "When I drew the pictures, they understood.”

Today Piscitelli shares this story when he speaks to trauma survivors and vets about art therapy. While his talent is in sculpture, he says any creative expression can help someone speak the unspeakable.

"There is a way," he tells them. "Nothing is hopeless.”

After leaving the veterans hospital, Piscitelli began art classes at the University of Massachusetts. There he found a kindred soul in art instructor Phillips, a combat pilot shot down over Laos during the war.

``All the sculpture faculty noticed his talent," Phillips said. ``He was remarkable.”

Phillips noticed other things about his student. Sudden noises, like the popping of a welding torch, made Piscitelli nervous. ``It was very obvious he was very shaky," Phillips said. ``He'd get a wild look in his eye."

But Piscitelli had a passion for his work and an eye for detail that helped him take on projects so complicated that some faculty couldn't complete them. Before he graduated, he completed a life-sized bronze statue of a soldier holding a fallen comrade. The piece was unveiled at a ceremony attended by Gen. William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. troops in Vietnam.

Piscitelli didn't sign that first piece because he wanted the emphasis to be on the soldiers, not the art. But he added a personal touch. The face of the soldier caring for his wounded friend is familiar. It's Steve Piscitelli’s.

CLASSICAL PIANO MUSIC ECHOES off the brick walls and full-length mirrors in the rehearsal studio. Dancers in T-shirts and tights stretch and bend in ways that no normal human could. Sitting on a bench in front of them, Steve Pi the artist slowly peels wax off the leg of a sculpture in front of him. He glances from his work to the dancers and back, making mental notes of the exact position of a foot or the particular muscle definition in a leg.

Pi knows every detail of a combat soldier, but he admits he knows very little about dance. He wants his dance artwork to be as accurate as his war pieces, so he spends hours at rehearsals and performances studying his subjects.

Before rehearsal, it's not unusual to see Pi sitting on the floor with a group of dancers, showing them his works in progress. They ask questions and often offer advice on adjusting a figure to obtain the perfect pose. More than a half dozen dancers at Southern Ballet Theatre have been subjects for Pi's work.

``It's a lot nicer to work with ballerinas than soldiers," Pi said. ``It's not painful at all.”

Pi continues to undergo art therapy and other counseling for post-traumatic stress. His artwork has been the primary source of his recovery. He says that every time he puts another war scene into bronze, it is easier to accept what happened, to survive it. ``Once it's out, it becomes a part of art, and it's frozen in this image, and it doesn't keep replaying in the mind," he explained.

Pi is now at work on his largest project. A few months ago, he saw a personal ad in a veterans magazine looking for men who had served with Dan Bullock. A childhood friend was trying to raise money to build a memorial to the youngest American soldier killed in Vietnam.

Pi is now creating that memorial. It will show Dan standing in front of bullet-pocked wall, holding a rifle, ready to bravely go around the wall during a raid. The teenager's figure stands tall, but it is dirty and weary rather than glorious. Organizers say the exceptionally realistic portrayal of war will ensure that the young Marine is not forgotten.

For Pi, Dan's sculpture will be another memory purged from his life and put on display so that people might somehow begin to understand.

Pi says he says he can't live long enough to put all of his demons into art. But he says he will never stop creating. Because every piece is a personal release -- and a reassurance that there is still beauty in the world.

This story originally appeared in Florida Magazine.